'Our Goal Is Not to Determine Which Version Is Correct but to Explore the Variability'

The International Linguistic Convergence Laboratory at the HSE Faculty of Humanities studies the processes of convergence among languages spoken in regions with mixed, multiethnic populations. Research conducted by linguists at HSE University contributes to understanding the history of language development and explores how languages are perceived and used in multilingual environments. George Moroz, head of the laboratory, shares more details in an interview with the HSE News Service.

— How did the laboratory's work begin?

— The laboratory was established in 2017, with Nina Dobrushina as its head and Johanna Nichols, Professor at the University of California, Berkeley, serving as Academic Supervisor. Prof. Nichols continues in this role remotely. Most of the researchers at the laboratory studied the languages of the Caucasus and the processes of convergence among them. For example, Nina Dobrushina, Michael Daniel, and Timur Maisak focused primarily on Dagestan, while Yury Lander and Anastasia Panova studied the Abkhaz-Adyghe languages.

One of the laboratory’s core research areas is linguistic typology, which involves classifying languages based on various criteria, such as the number of vowels and consonants. To this end, samples are collected that may include dozens of languages. Our laboratory is one of the few research centres in Russia conducting such studies—and perhaps the only one that focuses specifically on linguistic convergence. The laboratory also continues its research on the languages spoken in the Caucasus and the development of linguistic resources for them.

In the Caucasus, Russian comes into contact with languages spoken by a diverse range of groups. These include the Nakh-Dagestanian languages; Turkic languages spoken in Dagestan such as Kumyk and Azerbaijani; as well as Abkhaz-Adyghe languages (Abkhazian, Abaza, Adyghe, and Kabardian); Kartvelian languages (Georgian, Megrelian, Svan, and Laz); and Indo-European languages (Armenian, Ossetian, and Tat).

The primary purpose of establishing the laboratory has been to study the mutual influence of languages on one another. A striking example is the Ossetian language, which, although Indo-European, features ejective consonants—unlike other Indo-European languages. These are consonants produced by closing the vocal cords to build up pressure, which is then released abruptly—for example, [k'], [p'], [t'], [ts'], and [tʃ']. Additionally, during an expedition to Azerbaijan, the laboratory staff studied dialects in the regions bordering Dagestan, and Mikhail Daniel discovered a dialect of Azerbaijani featuring ejective sounds (admittedly, this had also been mentioned in earlier reports). This is likely explained by the fact that the ancestors of people now living in the village of Ilisu once spoke a Nakh-Dagestanian language—presumably Tsakhur—and later shifted to Azerbaijani, retaining traces of their original language in the form of ejective consonants. Most likely, this occurred as a result of language contacts.

A similar hypothesis was put forward by our academic supervisor, Johanna Nichols, about the inhabitants of some villages in Dagestan. While the Avar language is widespread in the north of Dagestan, mainly in the lowlands, native speakers of Avar can still be found in mountainous villages surrounded by non-Avar communities. It is possible that these Avar speakers originally used other languages and later shifted to Avar due to its social prestige.

The process by which languages borrow from one another or even shift entirely, leading to the blending of languages or dialects, is known as linguistic convergence. Although this process is easier to observe in genetically unrelated languages, a similar phenomenon can also occur among related languages or dialects.

— Does convergence always occur between neighbouring languages?

— It occurs in most cases, but there are also instances where languages and their speakers 'seek' to differentiate themselves from one another. This is called linguistic divergence. Last year, we invited John Mansfield to speak at our seminar. Together with his colleagues, he published a typological study on linguistic divergence processes, drawing on data from 42 languages worldwide.

— You mentioned Dagestan, a region where many languages are spoken. Could you tell us more about this area and your research related to it?

— Dagestan is remarkable for its multilingualism and the mutual influence of its local languages. At the same time, these languages have also begun to change under the influence of Russian, which has increasingly penetrated the local linguistic environment.

Together with our research assistant Victoria Zubkova and research fellow Chiara Naccarato, I recently submitted a paper to a leading international linguistics journal on the adaptation of Russian borrowings in the languages of the Andic branch of the Nakh-Dagestanian language family. Earlier, most loanwords entered these languages primarily through Avar serving as an intermediary. But now, borrowings often come directly from Russian. We are currently developing models to identify which languages are more influenced by Russian and what factors determine the extent of this influence.

In the course of this research, we found that recent Russian loanwords in Avar and Botlikh undergo fewer phonetic changes than in other Andic languages—for example, the Akhvakh word for kopeika (kopeck) is кIебекIиi. The primary reason is that these languages have already been significantly influenced by Russian. Avar historically played an important role in northern Dagestan and continues to serve as a regional lingua franca. The findings of our study indicate that the adaptation of Russian loanwords in other Andic languages occurred more slowly than in Avar, but this process has clearly accelerated over time. Nowadays, borrowings are likely to enter all these languages without any phonetic adaptation.

— How do you acquire the materials needed for your research?

—We regularly conduct field expeditions to collect data, which is our most important source of material. Our colleagues recently returned from Armenia, and another team from Adygea. Recently, we have begun to make more active use of data collected by researchers outside of our laboratory.

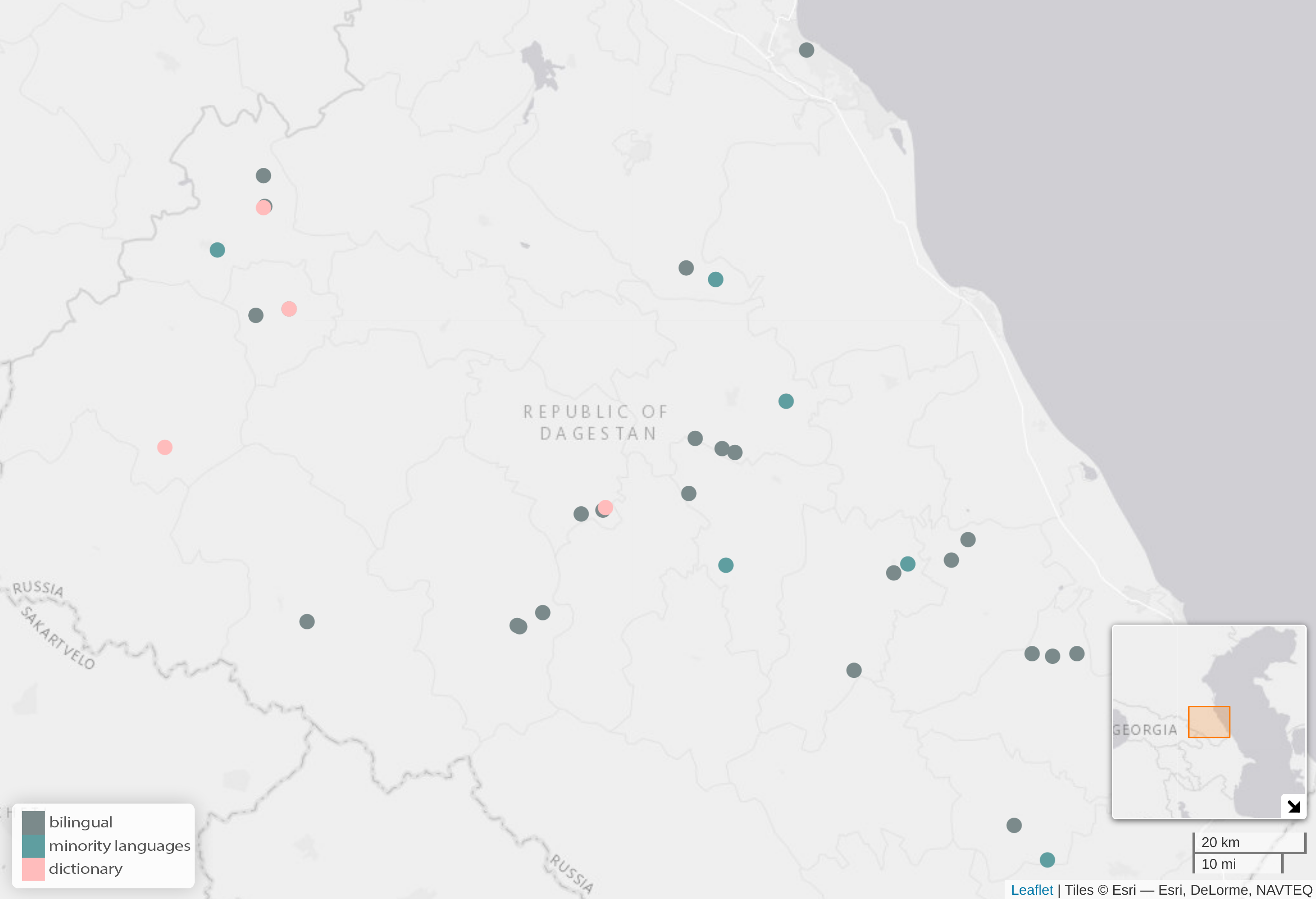

Our laboratory has compiled 10 spoken corpora of bilinguals—people whose native language is not Russian but who have learned and regularly use it in daily life. Their speech—both in pronunciation and grammar—differs from that of monolingual speakers.

Corpora of individual Russian dialects are also being developed. The main challenge in collecting such material has been that Russian dialectologists were traditionally reluctant to share their data with us. Thanks to Nina Dobrushina, this has changed, and it is now standard practice for them to publish their dialect corpora with us. A total of 26 dialect corpora have been created in our laboratory.

We have also been compiling corpora of minority languages spoken in Russia and have already created 14 of them.

— Could you explain what the term corpus means to linguists? How and why do you create new corpora?

— Corpora are collections of written records of various types of speech, or simply annotated text collections. What distinguishes a corpus from a mere collection of texts is the presence of morphological or other linguistic markup. In particular, a corpus can be searched by category, such as finding which nouns precede infinitives. The Russian National Corpus, for example, is an extensive collection of texts that supports morphological searches. When preparing spoken corpora—whether bilingual or dialectal—we use transcriptions in standard Russian, which enables automatic morphological searches. In addition, our corpora include audio recordings that allow users to explore the unique features of dialects. Sometimes, it is necessary to listen to a recording several times to accurately determine whether specific sounds are present.

Corpora are central tools in modern linguistics. By analysing the frequency of various constructions within them, we can draw generalisations that form the basis of our published research.

One way to use corpora is to compare dialects or minority languages; using vector models, we can observe the overlap between their corpora and thereby determine which dialects and languages are more closely related and which are more distant.

Thus, based on our observations of bilingual corpora, the Russian spoken by Karelians is closer to standard Russian than the Russian spoken by Dagestanis. In Dagestan, local languages are influenced both by standard literary Russian and by a regional Dagestani variety of Russian, which originated in the republic and is evolving in a distinctive way. What matters for children is the amount of language they use. For example, if Lezgins speak Lezgian and Adygs speak Adyghe or Kabardian before switching to Russian, one might wonder which variety of Russian they speak—standard literary Russian or a local version influenced by features from their native languages. Our corpora make it possible to compare these specifics.

— What other resources have you been creating?

— As I mentioned earlier, the laboratory’s key resources include linguistic atlases for minority languages in Russia.

We also compile dictionaries for such languages. For example, we recently published a dictionary of Kina Rutul, spoken by native speakers in Dagestan and Azerbaijan, featuring approximately 1,200 words. I have analysed the Zilo dialect of Andi—a dialect that lacked a written form for a long time—and uploaded a dictionary of about 1,500 of its words to the laboratory's webpage. However, this is a much smaller dictionary compared to those produced by linguists native to the regions where the languages are spoken, as they often have a stronger command of the local language and more time to dedicate to this task.

Dictionaries published in Dagestan typically contain at least 5,000 to 6,000 entries. Recently, our colleague Prof. Madzhid Khalilov published an 11,000-word dictionary of Tsez (Dido), a language spoken in Dagestan—a phenomenal achievement for an unwritten language.

— What are the key focus areas of the laboratory's current work?

— Our core research area is linguistic typology, based on analysing samples of unrelated languages from around the world.

Another ongoing long-term project is the Typological Atlas of the Languages of Dagestan, which currently includes 58 chapters, each dedicated to a specific linguistic feature—such as the presence or absence of certain ejective consonants. Samira Verhees and Chiara Naccarato, research fellows at our laboratory, studied how speakers of different languages greet each other in the morning, and contributed a chapter on this topic. They found that in 17 languages, alongside 'Good morning!', the rhetorical question 'Did you wake up?' is also common, and in the Lak language, both greetings are used.

A key area of focus is the development of electronic dictionaries for the languages spoken in Dagestan. We are creating a unified database that will contain the lexical material of the Nakh-Dagestanian language family. The database originated from a series of term papers by students in the Fundamental and Computational Linguistics programme, who digitised and cleaned the data and developed a transliteration tool. Their papers include phonetic and morphological markups, as well as markups of borrowings from Russian, Arabic, Persian and Turkic languages. At present, we have unified materials on the Andic languages and Avar.

This greatly facilitates studies that require the use of multiple dictionaries. The previously mentioned paper by Victoria Zubkova and Chiara Naccarato was made possible thanks to this database, which also creates new avenues for research. This project holds great potential, and I hope it will continue.

Another important research area is the study of non-standard Russian, which includes both regional dialects and the characteristics of Russian as spoken by non-native speakers. We refer to this group as DiaL2, where 'Dia' means dialects and 'L2' denotes second language. We are interested in all variations that differ from the standard forms. Our goal is not to determine which version is ‘correct,’ but rather to explore the variability we observe. Our group includes both laboratory researchers and students. Recently, our research assistant Anna Grishanova had a paper accepted for publication on the phenomenon of preposition drop in the Russian speech of Chuvash bilinguals.

There is a separate Rutul project. As part of the Rediscovering Russia grant, we visited 12 Rutul villages and produced an atlas similar to the Typological Atlas of the Languages of Dagestan I mentioned earlier. The Atlas of Rutul Dialects contains 425 chapters, each dedicated to different aspects of dialectal variation, including lexicon, phonetics, morphology, and syntax. For example, one chapter focuses on the lexical item for hedgehog, which has different variants in Rutul dialects, including a Russian loanword alongside native terms such as ɢɨˤllɨnc’, kʲirpikʲ, žüže, and k’ɨˤnʁɨˤr.

There are two smaller projects: one on the Aramaic languages spoken in Russia, supported by a Russian Science Foundation grant (24-28-01009) and titled 'Areal and Typological Description of the Neo-Aramaic Varieties in Armenia,' led by Yuri Koryakov; and a second project focusing on the Abkhaz-Adyghe languages.

Generally speaking, language documentation is crucial for the cultures we work with. Some unwritten languages may disappear, but if we document them in time, future generations will have the opportunity to learn how their grandparents spoke, even if they no longer understand their native language.

— How is the laboratory's work organised?

— I believe that the weekly seminars held every Tuesday at 4 pm are one of the pillars of our laboratory. Since its inception, the laboratory has hosted over 230 seminars, featuring nearly 300 presentations. Almost all seminars are conducted in English, which gives us more opportunities to involve international colleagues and maintain academic connections. We have been visited by renowned international linguists, such as Martin Haspelmath, a leading expert in linguistic typology. During his trip to Moscow last December, he gave a talk at HSE University that generated great interest. The seminars also provide guidance to our research assistants on how to make presentations, ask questions, and generally conduct themselves during discussions in English. Since I became head of the laboratory, we have increasingly used seminars as a platform to discuss new academic papers. This stems from my strong belief that it is all too easy to stop reading papers altogether, or to restrict ourselves to a narrow specialisation and produce new papers mechanically. However, reading and discussing others’ papers—even those far from one’s own research—helps us maintain a broad perspective on linguistics, rather than getting lost in details, much like the parable of the blind sages and the elephant.

— How actively do you collaborate with other universities and HSE campuses?

— As part of the Mirror Laboratories project, we collaborated with Southern Federal University from 2022 to 2024. Our joint efforts included three sub-projects: one focused on studying Russian as a foreign language; a dialectology project that allowed us to compile and maintain a corpus of dialects spoken in the villages along the Don River, which we might continue; and a Digital Humanities (DH) project.

Digital Humanities are at the core of a current inter-campus project with HSE University in St Petersburg. Together with colleagues, we focus on applied computational linguistics. Specifically, in St Petersburg, they created a corpus of Russian short stories from 1930 to 2000, compiled a corpus of Soviet songs, and even developed a chatbot for the Hermitage Museum.

— What is the operating principle behind this chatbot?

— For example, a visitor might ask to see a painting depicting a woman holding a plate with a head on it, referring to Judith with the head of Holofernes; the chatbot is designed to retrieve the corresponding image. However, hardly anyone would be surprised if the result turned out to be Herodias with the head of John the Baptist.

— Are there other examples of applied work you could highlight?

— We have several ongoing applied research projects. For example, we have begun developing transliterators for the Nakh-Dagestanian languages. Our goal is to create a hub offering transliteration tools for texts in various languages, which would be highly valuable for linguists.

Additionally, we are developing morphological analysers for minority languages, as well as compiling corpora and dictionaries. Ultimately, all of this provides rich material for validating machine learning models across different modalities, including both audio and text. Such models often suffer from a shortage of expert data markup.

Michael Daniel

Nina Dobrushina

Anastasia Panova

See also:

HSE Psycholinguists Launch Digital Tool to Spot Dyslexia in Children

Specialists from HSE University's Centre for Language and Brain have introduced LexiMetr, a new digital tool for diagnosing dyslexia in primary school students. This is the first standardised application in Russia that enables fast and reliable assessment of children’s reading skills to identify dyslexia or the risk of developing it. The application is available on the RuStore platform and runs on Android tablets.

Physicists Propose New Mechanism to Enhance Superconductivity with 'Quantum Glue'

A team of researchers, including scientists from HSE MIEM, has demonstrated that defects in a material can enhance, rather than hinder, superconductivity. This occurs through interaction between defective and cleaner regions, which creates a 'quantum glue'—a uniform component that binds distinct superconducting regions into a single network. Calculations confirm that this mechanism could aid in developing superconductors that operate at higher temperatures. The study has been published in Communications Physics.

Neural Network Trained to Predict Crises in Russian Stock Market

Economists from HSE University have developed a neural network model that can predict the onset of a short-term stock market crisis with over 83% accuracy, one day in advance. The model performs well even on complex, imbalanced data and incorporates not only economic indicators but also investor sentiment. The paper by Tamara Teplova, Maksim Fayzulin, and Aleksei Kurkin from the Centre for Financial Research and Data Analytics at the HSE Faculty of Economic Sciences has been published in Socio-Economic Planning Sciences.

Mistakes That Explain Everything: Scientists Discuss the Future of Psycholinguistics

Today, global linguistics is undergoing a ‘multilingual revolution.’ The era of English-language dominance in the cognitive sciences is drawing to a close as researchers increasingly turn their attention to the diversity of world languages. Moreover, multilingualism is shifting from an exotic phenomenon to the norm—a change that is transforming our understanding of human cognitive abilities. The future of experimental linguistics was the focus of a recent discussion at HSE University.

Larger Groups of Students Use AI More Effectively in Learning

Researchers at the Institute of Education and the Faculty of Economic Sciences at HSE University have studied what factors determine the success of student group projects when they are completed with the help of artificial intelligence (AI). Their findings suggest that, in addition to the knowledge level of the team members, the size of the group also plays a significant role—the larger it is, the more efficient the process becomes. The study was published in Innovations in Education and Teaching International.

New Models for Studying Diseases: From Petri Dishes to Organs-on-a-Chip

Biologists from HSE University, in collaboration with researchers from the Kulakov National Medical Research Centre for Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Perinatology, have used advanced microfluidic technologies to study preeclampsia—one of the most dangerous pregnancy complications, posing serious risks to the life and health of both mother and child. In a paper published in BioChip Journal, the researchers review modern cellular models—including advanced placenta-on-a-chip technologies—that offer deeper insights into the mechanisms of the disorder and support the development of effective treatments.

Using Two Cryptocurrencies Enhances Volatility Forecasting

Researchers from the HSE Faculty of Economic Sciences have found that Bitcoin price volatility can be effectively predicted using Ethereum, the second-most popular cryptocurrency. Incorporating Ethereum into a predictive model reduces the forecast error to 23%, outperforming neural networks and other complex algorithms. The article has been published in Applied Econometrics.

Administrative Staff Are Crucial to University Efficiency—But Only in Teaching-Oriented Institutions

An international team of researchers, including scholars from HSE University, has analysed how the number of non-academic staff affects a university’s performance. The study found that the outcome depends on the institution’s profile: in research universities, the share of administrative and support staff has no effect on efficiency, whereas in teaching-oriented universities, there is a positive correlation. The findings have been published in Applied Economics.

Advancing Personalised Therapy for More Effective Cancer Treatment

Researchers from the International Laboratory of Microphysiological Systems at HSE University's Faculty of Biology and Biotechnology are developing methods to reduce tumour cell resistance to drugs and to create more effective, personalised cancer treatments. In this interview with the HSE News Service, Diana Maltseva, Head of the Laboratory, talks about their work.

Physicists at HSE University Reveal How Vortices Behave in Two-Dimensional Turbulence

Researchers from the Landau Institute for Theoretical Physics of the Russian Academy of Sciences and the HSE University's Faculty of Physics have discovered how external forces affect the behaviour of turbulent flows. The scientists showed that even a small external torque can stabilise the system and extend the lifetime of large vortices. These findings may improve the accuracy of models of atmospheric and oceanic circulation. The paper has been published in Physics of Fluids.